Major Works and Positions

- Evening Star columnist

- Living Way (1887)

- Elected Secretary For Afro-American Press Association (1889)

- Invited to become editor of and co-publisher of the The Memphis Free Speech and Headlight (1889)

- New York Age (June 7, 1892)

- The Reason Why the Colored American is not in the World Columbian Exposition

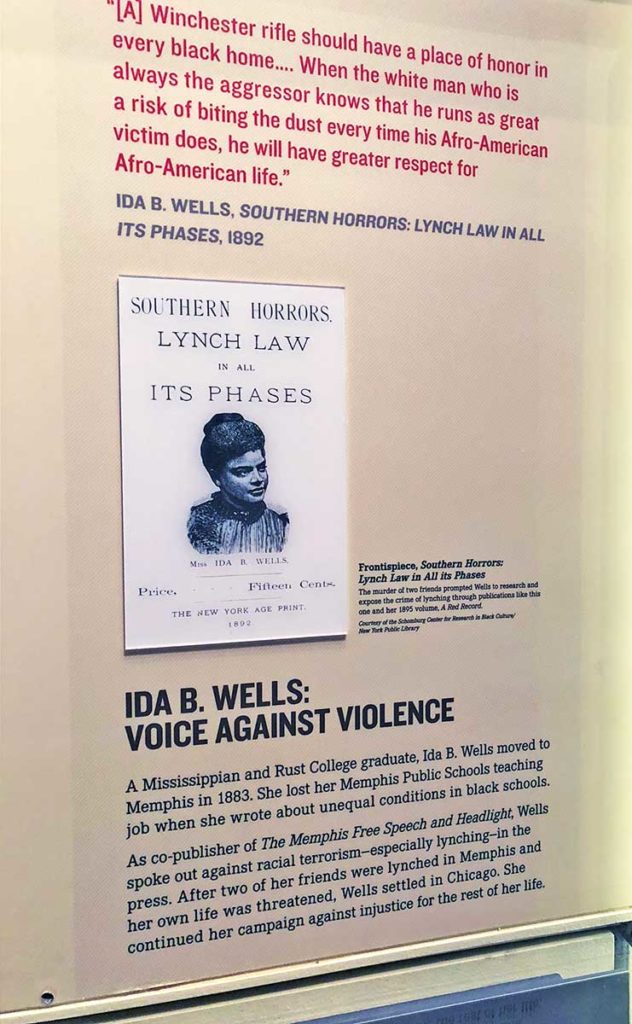

- Southern Horrors: Lynch Law in All Its Phases (1892)

- Chicago Conservator (1893)

- Crusade for Justice

Biography of Ida B Wells-Barnett

Ida B. Wells panel at the Lorraine Motel National Civil Rights Museum in Tennessee. Photo by K. Jacobs

Ida B. Wells was born in Holly Springs, Mississippi. Numerous sources incorrectly list her birthplace as Holly Springs, Missouri, however. Born a slave along with her parents near the end of the Civil War, her father was a carpenter, and her mother was a famous cook. She was the oldest of four boys and four girls.

She received her education at Rust College, a freemen’s high school and industrial school. She moved to Memphis in 1883 where she taught at the Memphis Public Schools.

In 1887 yellow fever left her and her sisters and brothers without their parents, and she managed with her father’s savings to support their family (Notable Black American Women 1232).

When she was forced to give up her first class seat on the Chesapeake Railroad car in 1884, she filed a lawsuit against the company and became the first Southern black to appeal to a state court since the Supreme Court’s Civil Rights case in 1883.

The lower court ruled in Barnett’s favor, but the decision was reversed by the Tennessee Supreme Court in 1887. She decided to tell the story of her lawsuit in the black church weekly, The Living Way.

In 1887 she was made the secretary of the Afro-American Press Association, and she was the first woman representative to attend conclave. She became part-owner of the The Memphis Free Speech and Headlight in charge of the editorial operations (African American Civil Rights 37).

Ida B.Wells began a crusade against lynching, which caused a white mob to destroy her newspaper office. She was asked by Timothy Thomas Fortune to work at his newspaper office to continue her anti-lynching campaign.

She organized the Woman Loyal in Brooklyn, N.Y, the first black woman anti-lynching club and established similar anti-lynching clubs in Boston, Massachusetts, Washington, D.C. and other cities.

She organized the first black women’s suffrage group, and in 1909 she was among the blacks and whites who founded the NAACP ( African- American Civil Right 37).

On March 21, 1931, Wells-Barnett became ill and was rushed to the Daily Hospital. On March 23 she was found to be suffering from uremic poison. On March 25 at the age sixty- nine, she passed away and was buried in Chicago’s Oakwood Cemetery.

As a black American leader of the nineteenth and twentieth century, the life of Wells has been memorialized. In 1941 the Chicago Housing Authority opened the Ida B. Wells Housing Project, and in 1950 the city of Chicago named her one of twenty-five outstanding women in the city’s history (Notable Black American Women 1237).

Summary of Crusade for Justice

by Lavon Williams (SHS)

Crusade for Justice is the autobiography of Ida B. Wells (1862- 1931), who was born prior to the Emancipation Proclamation, and left alone to rear eight children after her parents’ death. In the early 1880’s, she moved to Memphis where she became a school teacher in the rural part of Shelby County, Tennessee.

On May 4, 1884, Wells was traveling by train to Woodstock, Tennessee, where her school was located. She purchased a first class ticket, and the train conductor ordered her to move to the smoking car. She refused, and the conductor asked several white passengers to remove her from the car.

When she returned to Memphis, she filed a lawsuit against the railroad company. It was the first time a Southern black had filed an appeal to a state court since the United States Court declared unconstitutional the Civil Rights Act in 1875. She won the lawsuit, but the railroad appealed and the Supreme Court reversed the decision of the lower court.

Wells was disappointed because she had great hopes for her people. During the same year, she passed the qualifying examinations and became a teacher. In 1887 she wrote the article about her suit against the railroad.

She became part owner of the city’s only Afro-American Journal, Free Speech and Headlight. The article criticized the Memphis Board of Education for Separate Inferior Negro schools and that led to her dismissal in 1891. She became a full-time journalist, encouraging boycotts and urging blacks to leave Memphis.

In 1892 she denounced the lynching of three young black businessmen. Her editorial office was wrecked after the article. She then began working at the New York Age and began to write against the South. She moved to Chicago in 1895 where she published A Red Record: Tabulated Statistics and Alleged Cause of Lynching in the United States 1892-1894. The book represented the first serious recording of lynching.

Wells married African-American rights advocate Ferdinand Barnett, and the couple published the Chicago Conservator. They were considered pillars of the black community of Chicago. Ida B. Wells-Barnett had several children, including Ida B. Wells, Jr.

Barnett established the first black women’s suffrage group called the Alpha Suffrage Club, which demanded the right to vote. She was also one of the founders of the Niagara Movement. It evolved into the NAACP.

She began speaking out for “federal anti-lynching laws, universal suffrage, quality education, and an end to discrimination and segregation.” In 1913 Wells was the first black probation officer with Chicago Municipal Court. Chicago’s Housing Authority named one of its lowest income housing developments after her in 1941.

Ida Wells died in 1931 of illness. Later (in 1970) Crusade for Justice: The Autobiography of Ida B. Wells was edited by her daughter and was published. It is a story every American should read.

Related Websites

- Bio website on Ida B. Wells

- Ida B. Wells-Barnett House

- Duke University page “Ida B. Wells-Barnett and Her Passion for Justice” by Lee D. Baker

- PBS story on Ida B Wells

Bibliography

- “African- American Civil Rights.” Westport: Greenwood Press, 1992.

- “Black Americans” New York, NY: Facts of Files, Inc, 1992.

- “Extraordinary Black Americans” Canada: Childrens Press, 1989.

- “Notable Black American Women” Detroit, Mi: Gale Research, 1992.