Major Works

- Haiku: This Other World (1998) with an introduction by his daughter Julia.

- Early Works: Lawd Today!, Uncle Tom’s Children, Native Son (New York: Library of America, 1991)

- Later Works: Black Boy (American Hunger), The Outsider. (New York: Library of America, 1991)

- Richard Wright Reader. Ed. Ellen Wright and Michel Fabre (New York: Harper and Row, 1978)

- American Hunger (New York: Harper and Row, 1977)

- Lawd Today (New York: Walker, 1963)

- Eight Men (Cleveland: World, 1961)

- Pagan Spain (New York: Harper, 1957)

- The Long Dream (Garden City, N.Y.: Doubleday, 1957)

- White Man, Listen! (Garden City, N.Y.: Doubleday, 1957)

- Savage Holiday (New York: Avon, 1954)

- Black Power: A Record of Reaction in a Land of Pathos (New York: Harper, 1954)

- The Outsider (New York: Harper, 1953)

- Black Boy: A Record of Childhood and Youth (New York: Harper, 1945)

- Native Son (The Biography of a Young American): A Play in Ten Scenes. With Paul Green. (New York: Harper, 1941)

- Bright and Morning Star (New York: International Publishers, 1941)

- 12 Million Black Voices. With photo-direction by Edwin Rosskam. New York: Viking, 1941. Cinque Uomini. Milan: Mondadori, 1951.

- Native Son (1940)

- Uncle Tom’s Children: Four Novellas (New York: Harper, 1938)

- The Color Curtain: A Report on the Bandung Conference.

Richard Wright: A Biography

by Quinisha Logan (SHS)

Deep in the southern states of America, when this country struggled with changes, people not only suffered from poverty, hunger, and illnesses, but people endured racism and violence. These experiences colored people’s lives forever. Richard Nathaniel Wright was no exception. Out of the hardships and unpleasantness, Richard Wright formed ideas which became the central themes of his literary work.

Richard Wright was born in the backwoods of Mississippi on Rucker’s plantation, twenty-five miles from Natchez, on September 8, 1908, near the community of Roxie. Wright was born to an illiterate sharecropper father, Nathaniel Wright, and a school teacher mother, Ella Wilson Wright. Richard Wright’s roots are buried within the black, white, and Choctaw Indian races.

While Wright was still a toddler, Ella Wright also gave birth to Leon Alan Wright, Richard’s brother. Within a year to two years after Leon’s birth, the Wright began their long quest for a better life. Between the years 1911 and 1912, Ella Wright decided to leave the farm with her children. Ella Wright and her two sons traveled twenty-five miles to Natchez. Once in Natchez, they lived with Ella Wright’s family, the Wilsons. While living with the Wilsons, Richard accidentally set fire to his grandparents’ home.

After Nathaniel Wright’s hard work failed to produce a profit on his “rented” farm, he moved his family to Memphis, Tennessee. Upon arrival in Memphis, the Wright family took residence in a two-room tenement, which was not far from Beale Street. This city, which was filled with brothels, saloons, and storefront churches, forced Richard to encounter the terrors of crime, violence, and racism.

While growing up in Memphis, Richard felt the absence of his father more and more. . When Richard reached the age of six years old, his father deserted the family and lived with another woman. The desertion of Richard Wright’s father forced Richard to face another terror: poverty. “The image of my father became associated with the pangs of hunger,” wrote Wright in Black Boy, his autobiography, “Whenever I felt hunger, I thought of him with a deep biological bitterness.” With the heavy weight of supporting her family of three upon her shoulders, Ella Wright found jobs working as a housemaid and a cook. In the year 1915 Ella became ill, and her sons were forced to move into an orphanage.

Although Wright’s stay in the orphanage was brief, it was memorable. Once Wright left the orphanage, he attended school briefly at the Howard Institute. As time progressed, Ella Wright’s health worsened, forcing the Wright family to live with Ella’s sister and brother-in-law, Maggie and Silas Hopkins in Arkansas. Richard developed a close bond with his uncle Silas. However, Silas Hopkins, who was a prosperous builder and saloon-keeper, was murdered by some white people in 1917. Because no arrests were made, Maggie Hopkins, Ella Wright, and the children escaped to West Helena, Arkansas. During this time, money was scarce. Richard Wright left school in order to find work. Ella Wright’s health continued to deteriorate, and she eventually suffered from a stroke and became paralyzed.

Because of these tragic circumstances, Richard and Leon were separated. Richard Wright moved back to Mississippi, where he lived with an aunt and uncle in Greenwood. He then returned to Jackson because he was unhappy. There he lived with his religious grandparents and aunt Addis, who were members of the Seventh-Day Adventists. He did not share in their attitude toward religion. Because of this he felt that he was an outsider in their home. While at his grandparents’ home, he attended the Seventh-Day Adventist school that was taught by Addie. The strict rules caused him to rebel. A year later he transferred to Jim Hill School, a public school, where he excelled academically.

In the year of 1923, Wright attended Smith Robertson Junior High School where he published his first short story “The Voodoo of Hill’s Half-Acre” in the Jackson Southern Register. Because this story was inspired by local folklore, country sermons, and popular literature, his family criticized the piece, making Wright determined to become a writer.

Richard Wright graduated from Smith-Robertson Junior High School as class valedictorian, and at the age of seventeen he returned to Memphis with a ninth-grade education and a small amount of money. After Wright had lived in Memphis for two years, Ella Wright and Leon Wright joined him.

Although his stay in Memphis was not long, Richard Wright became acquainted with the works of writers whose prose changed Richard’s view of literature. Richard Wright began to study the work of H. L. Mencken. From Mencken, “Wright learned that words could serve as weapons with which to lash out at the world” (Contemporary Black Biography 294). Richard Wright’s study of Mencken led to the study of American naturalist writers such as Theodore Dreiser, Sherwood Anderson, and Sinclair Lewis. However, Richard Wright did not feel that his private studies were enough to keep him in Memphis. Accompanied by his aunt Maggie, he boarded a train that was bound for Chicago.

Although Richard Wright moved to a northern state where he hoped to escape from racial discrimination and other social injustices, his struggle continued. Richard Wright’s mother and brother joined him in Chicago where Wright quickly became bored with high school. After seeing no reason to continue his education, Richard Wright left school and obtained jobs in order to help support the family. The odd jobs that he obtained left him “many hats.” Wright worked as a dishwasher, a porter, a busboy, a street sweeper, a group leader at the South Side Boys Club, and a clerk at the Chicago Post Office. At the Chicago post office, Richard Wright became acquainted with many radical individuals. With the aid of some of these individuals, Wright became affiliated with the John Reed Club, a revolutionary writers’ organization. Wright’s associates encouraged him to pursue a career in writing. With his new inspiration, Richard Wright began to write poetry for various publications.

When Wright’s interest in race relations and radical thought increased, he joined the Communist party. For the first time in his life, Richard Wright felt that he found a peer group that shared the common goal of promoting racial and social equality. Wright stated in his contribution to the book The God That Failed, “It seemed to me that hear at last, in the realm of revolutionary expression, Negro experience could find a home, a functioning value and role.” His newfound happiness in the Communist party temporarily caused his loneliness to subside.

In 1935 Richard Wright traveled to New York City after the disbandment of the John Reed Clubs. While in New York City, he attended the American Writer’s Congress with other writers such as Langston Hughes, Malcolm Cooley, and Theodore Dreiser. He later returned to Chicago and found employment preparing guidebooks for the Federal Writer’s Project, a New Deal relief program for unemployed writers. In the beginning of 1936, Wright was transferred for a small period of time to the Federal Theater Project. In addition to these jobs, Richard Wright wrote for the Daily Worker. Feeling that his present writing was not enough to satisfy his hunger for writing, he began to work on a collection of short stories as well as write his first novel, Lawd Today. Unfortunately Richard Wright did not live to see Lawd Today published in 1963.

As his literary career expanded, conflicts with the Communist party grew. Richard Wright began to question the policies of Stalinism after he studied sociology, psychology, philosophy, and literature. More conflicts arose when he found that recruiting, organizing, and distributing party literature. In 1937, several Chicago Communists accused Richard Wright of betraying the Communist party. , Richard Wright tired of Chicago and moved to New York.

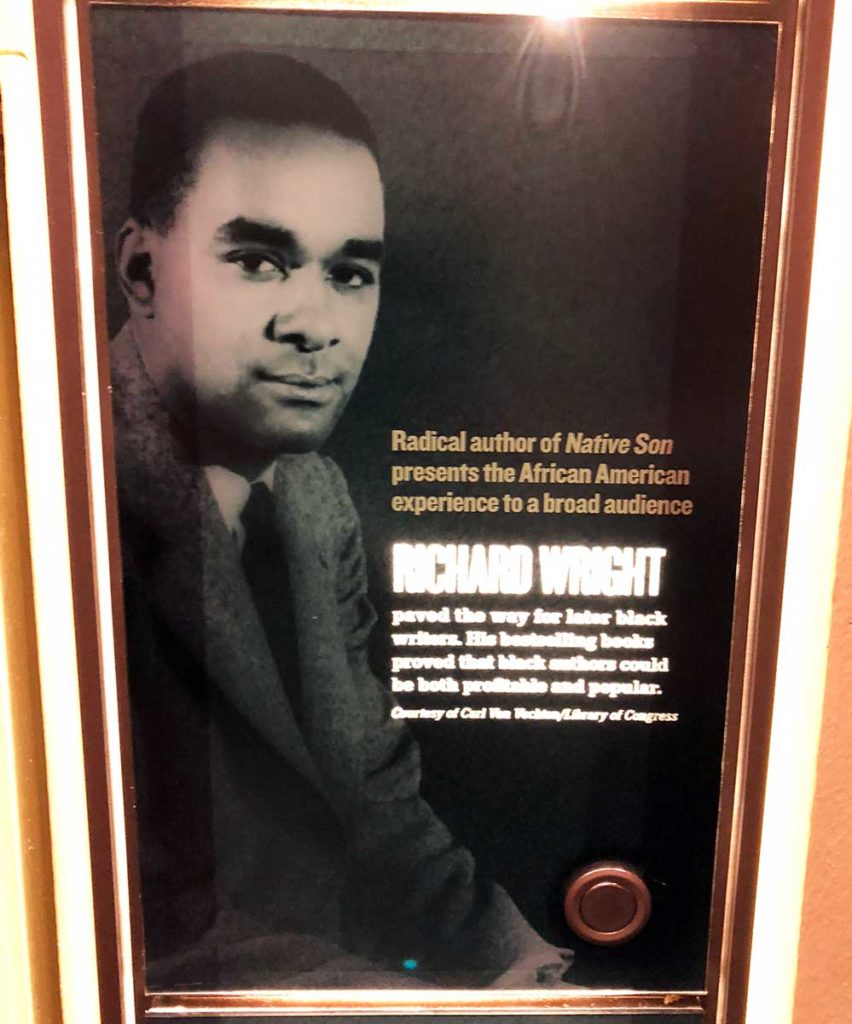

Wright had not been in New York for a long period of time when he published Uncle Tom’s Children. Richard Wright won a Works Progress Administration award for Uncle Tom’s Children in 1938. Uncle Tom’s Children received many good reviews. In the following year, Richard Wright married Dhima Rose Meadman, a ballet dancer. However, their marriage failed a year later. Later, Wright published Native Son, a Book-of-the-Month-Club selection, in 1940. Richard Wright sold over a quarter of a million copies of Native Son in six months. Native Son became Wright’s most famous and financially-successful book.

Wright’s life began to look promising. In 1941 Wright found someone that wanted to spend the remainder of his life with. His second wife was Ellen Poplar, a Communist organizer from Brooklyn. About this time Wright received the Springham Medal for Native Son from the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People. With the collaboration of Edwin Rosskan, Wright then completed Twelve Million Black Voices, his third book. In 1942 Ellen Poplar gave birth to his first child Julia. Her birth was followed by another great change in Wright’s life: his withdrawal from the Communist party. This break with the Communist party was not announced formally until 1944. Wright’s break with the Communist Party became known with the publication of “I Tried to be a Communist,” which could be found in The Atlantic Monthly, and “The Man Who Lived Underground,” which was published in Cross Section. Following his separation from the Communist party, Richard Wright published Black Boy, a book-of-the-Month selection that became a bestseller received excellent reviews.

After visiting France in May of 1946, Wright and his family decided to make France their final home. In 1947, the Wright family became a permanent expatriate of the United States of America. Richard Wright never returned to the United States of America again.

Following the birth of his second daughter Rachel in 1949,Wright published several novels. In 1953, The Outsider was published. The reviews Wright received for this novel were mixed. After returning from Spain in 1954, Richard Wright published Savage Holiday. In 1955, he returned to Spain and attended the Bandung Conference, which led to his writing The Color Curtain: A Report on The Bandung Conference. Also after his return from Spain, Richard Wright completed Pagan Spain and White Man Listen!. Although Richard Wright published many successful novels, Daddy Goodness, his last novel, received unfavorable reviews and was not successful. In 1960, Richard Wright abruptly died of a heart attack on November 28. Another Mississippi writer, Margaret Walker, has written a comprehensive book about Wright called Demonic Genius. It is little known that Wright wrote poetry, but in 1998 a book of 817 Haiku poems by Wright was published. Richard Wright wrote Haiku: This Other World during the last eighteen months of his life while living in France. The book, in addition, contains a fascinating introduction written by Wright’s daughter Julia, who today lives in Connecticut.

Richard Wright: A Biography

by Daniele Fleming (SHS)

Richard Wright was a novelist, short story writer, poet, and essayist. His works focused on issues dealing with blacks in the society of America. Through personal experiences, Wright was able to express the feelings and hardship of blacks in coping with discrimination. His works were known for the vivid details of the emotions blacks felt in a white society.

Richard Wright’s childhood is full of hardship and disappointment. After the abandonment by his father in Memphis, he became very aggressive and mischievous. Although the odds were against him, Richard managed to educate himself. He was first introduced to novels at an early age by a school teacher, Ms. Ella, who boarded in his grandmother’s home. Wright would sneak into Ms. Ella’s room and try to read novels from her collection. His grandmother, a strong and faithful member of the Seventh Day Adventists, felt that his disobedience and foul language was linked to his reading of the books. Therefore, Ms. Ella was put out for putting devilish ideas into Richard’s head. He was able to fulfill his growing hunger to read through the help of a white Jewish co-worker who lent Wright a whites-only library card. Wright focused on the works of H. L. Mencken, Sinclair Lewis, and Theodore Dreiser. Books satisfied the emotional being within him that was not developed from his childhood. The laws of society forced Wright to be defensive and hesitant to express his feelings about things around him.

Even though Richard Wright was limited in ways to expand his mind, he got his first opportunity to publish in 1924. The Voodoo of Hell’s Half Acre? a fictional short story about a villain’s strategy to gain a widow’s house, appeared in the Southern Register, a black newspaper. Because the locals did not understand Right’s motives for writing, future outbursts of the creative mind were discouraged by family members. However, this road block did not stop him. Wright went on to publish his first book, Uncle Tom’s Children, in 1938. Then in 1940 Wright published Native Son. The main character, Bigger Thomas, murders two white women because he feels it as a necessity. The plot stood as an example of how blacks felt their actions in life were in some way controlled by the whites. Wright was awarded the Spingarn Medal from the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People in 1940 for Native Son. The novel later was written for Broadway and a screenplay. Black Boy, an autobiography of Wright’s southern childhood, was published in 1945. It is considered his most important piece of work.

In 2017, Wright was inducted in to the Mississippi Arts + Entertainment Experience Hall of Fame.

Reviews

A Review of Black Boy

by Daniele Fleming (SHS)

Black Boy is an autobiography of Richard Wright. The novel covers his life from the age of about four to the train ride Richard makes from Memphis to Chicago. Wright tells how, during his childhood, he deals with the relationships between himself and whites and himself and his other family members.

Richard learns as he grows up, that to survive in the South, he must act and say things the way the South wants him to. Not only must he follow and respect his place as a black boy in a white society, but he must also keep his place in the black world of the South. Richard finds himself questioning events and traditions that others have accepted as true. Because of his inquiry, his actions are mostly seen as rebellious and troublesome. Richard states on the train ride to Arkansas, “My mother became very irritated when I questioned her about whites and blacks, and I could not understand it.” He also faces problems with the idea of religion. Richard’s grandmother, Granny, “an ardent member of the Seventh-Day Adventist Church,” made most of his childhood difficult because of their opposing views on the topic. While living with her, Richard felt “compelled to make a pretense of worshiping her God” when in fact he felt no need for religion in his life. These interactions with events in the South and crosses with ideas of others molds his life into thoughts to those of anger and revenge. When the book ends with his move to the North, Richard wonders if his view of things can be reversed or corrected in the North.

Richard spends most of his childhood days in Jackson, Mississippi, the home of Granny. Here is where most of the ideas and traditions affect him. Black Boy starts out at Granny’s house (then moves to Natchez), where Richard accidentally burns the house down. He is beaten severely by his mother. Next, the family moves to Memphis. Richard is introduced to violence, hunger, alcohol, and revengeful anger all at about the age of six. Because of lack of money and poverty, Richard, his mother, and brother, Leon, move to Elaine, Arkansas, the home of Aunt Maggie. He here comes in close contact with “white terror” in the South. This connection is made when his Uncle Hopkins is murdered by white men who made dealings with Hopkins and his saloon. From there, the family (including Aunt Maggie) return to Granny’s house, now in Jackson, Mississippi. Richard’s mother suffers from a “stroke of paralysis” and this results in Richard and his brother being split up and sent to different places to live. Because there was lack of money, Leon is taken up North; while Richard goes to live with his Uncle Clark and wife in Greenwood, Mississippi. Uncle Clark wants to give Richard his first full year of formal education; however, Richard wants to return to Jackson and be with his mother before the year ends. Now staying with Granny ( which is where his mother is) is more difficult than he thinks. For both Granny and Aunt Addie force Richard to believe in God and “save his soul.” After years of conflict in religious values, Richard leaves the household to be on his own. His destination is Memphis. The home of Mrs. Moss and her daughter Bess becomes his new dwelling. Richard is now able to live by his own judgment, save money, and expand his mind through books all for the first time.

Black Boy is written in first person, for Richard Wright tells of his encounters and learning experiences of the South. Wright tells his life in such a way that one can actually feel the emotion and understand the actual difficulty of growing up in the South. The clear and vivid descriptions used to describe conflicts and events make this so.

The whole theme of the book is clearly summed up at the end—“my feelings had already been formed by the South . . . that there was yet hope in that southern swamp of despair and violence, that light could emerge even out of the blackest of the southern night.” Wright uses his life to explain that the grips of the South and desperation it had back then can not hold the determination of the heart. One did not have to fall to the actions of the South, but one could take what he or she has learned and apply it to a better life.

I enjoyed the autobiography very much. Not only did it inform the reader of the life of Richard Wright, but it inspires the reader to overcome obstacles in life and become better despite harsh surroundings. This simple fact is probably the reason why Black Boy is considered Wright’s most important novel.

“Between the World and Me” An Analysis of Wright’s Poem

by Quinisha Logan (SHS)

Between the World and Me, a poem by Richard Wright, is about a man that experiences a victim’s death by looking at his charred skeleton. After reading the poem once, the reader may experience a deep sadness and regret for the victim of the burning. However, reading the poem several times, the author’s true meaning is apparent. When tragic situations happen, people view them with pity and remorse; but until people look at it from the victim’s prospective, they do not truly understand the situation. They are separated from the world. When the main character of Between the World and Me, mentally experiences the victim’s death, the author’s theme of the poem is illustrated.

The poem begins with the protagonist, who, while walking in the woods. stumbles across a charred skeleton on a tree. This initial scene symbolizes how society views tragedies. Typically society views adversities as a terrible misfortune. Although people are usually deeply saddened by the circumstances, they are generally lacking in understanding the victim’s view point and emotions. Until people can understand the situation from the victim’s prospective and the emotions that arose from the incident, the world is separated from the victim.

As the poem progresses, the protagonist continues the view the victim’s death from the point-of-view of an outsider. While the protagonist is “viewing” the victim’s death, he experiences a “cold pity for the life that was gone.” After the protagonist experiences this, the details of the victim’s death became more vivid. When “the dry bones stirred, rattled, lifted, melting themselves” into the protagonist’s bones, the main character truly understood the victim’s pain and situation. Once the protagonists become the victim mentally, the experiences of the victim become real. The protagonist visualizes that he can feel the pain as the victim’s murders “battered his teeth into his throat till he swallowed his own blood.”

Through the vivid details of this poem Wright’s theme becomes evident. Because it illustrates its theme well, the reader is connected to the protagonist. Throughout life many people feel remorse for the victims of tragedies. As it is demonstrated in this poem, a tragedy will occur, and one will became deeply in tune to the victim’s pain. After this happens, that person will have a different understanding of life and will be separated from the world figuratively.

A Review of “The Man Who Lived Underground“

by Quinisha Logan (SHS)

When the world was created, each person in it was created with different personalities. This difference in personalities. This difference in personalities causes the world to become diverse. Some individuals feel that people should act in the manner that they expect them to. Those individuals judge people by their stereotypes. In Richard Wright’s short story The Man Who Lived Underground, the protagonist escapes from society’s stereotype of an African American male by hiding underground. After the protagonist returns to “the worlds,” he experiences the ultimate punishment.

As the story opens, the protagonist is trying desperately to hide from the police. The police accuse the protagonist of murdering a Caucasian female. Although he is not guilty, he is forced to sign a confession. Feeling that hiding is his only escape, the protagonist escapes from jail. This brings the reader to the initial scene. The protagonist waits impatiently in the vestibule of a church as the police search foe him in the opposite direction of the church. When he feels that it is safe, the protagonist runs to a manhole cover and escapes into the sewer.

The protagonist’s adventures in the sewer teach him to use his survival skills. Throughout the protagonist’s stay in the underground, he endures the swift currents of the sewer, as well as having to exist off of food that he steals. During one incident, the protagonist enters into Nick’s Fruits and Meats through its basement. While he looks for food there, a Caucasian couple enters into the store. They mistake him for an assistant and purchase a pound of grapes. After they leave the store, he steps outside of the store. Once outside he reads a headline, which states “Hunt Negro for Murder.” At this time, the protagonist realizes the seriousness of the matter and that because he is African American he fits the stereotype of a murderer. Although he wants to prove his innocence, it cannot be done. Because if fear, he returns to the “underground.”

As the protagonist continues to travel through the underground, he obtains the combination to a jewelry store safe. Through using the combination, he steals thousands of dollars as well as jewels, rings, and watches. As a result of his crime, an innocent man takes his life because he was accused of the crime. Eventually the protagonist tires of running away from his problem. He returns to the police station where he was accused so that he could return to the world that deeply rejected him. In the end, the antagonists, or police, present the protagonist with a gift they feel he deeply deserves.

Although the plot is not filled with many physical conflicts, it contains many struggles with nature. This is evident through the protagonist’s struggle to survive the “underground.” This story also contains man verses man conflict. The protagonist struggles not to forget who he is. The protagonist also is tormented by the night watchman’s suicide and the claustrophobic feeling he receives while in his “hideout.” Although the plot moves slowly, it captures the attention of the reader by making the person wonder what will happen next. This short story is recommended for people who like to see man struggle within himself as well as with society.

Related Websites

- Biography.com page on Richard Wright

- Richard Wright obituary in the New York Times

- Critical Writers of the 20th Century

- The Enduring Importance of Richard Wright by Milton Moskowitz

Bibliography

- Chapman, Abraham. Black Voices. New York: New American Library, 1968.

- Cohassey, John. Contemporary Black Biography, 5 vols. 5: 293-296.

- Felgar, Robert. Richard Wright. Boston: Twayne Publishers, 1980.

- Mitgang, Herbert, “Richard Wright–collected and relevant,” Clarion Ledger. Detroit: Gale Research Company, 1985. 530-535.

- Wright, Richard. World Book Encyclopedia. Vol 21. 1996 ed.