Major Works

Plays

- Not About Nightingales. New York: New Directions, 1998.

- Something Cloudy, Something Clear. New York: New Directions, 1995.

- The Red Devil Battery Sign. New York: New Directions, 1988.

- Stopped Rocking and Other Screenplays. New York: New Directions, 1984.

- The Remarkable Rooming-House of Mme. LeMonde. New York: Albondocani Press, 1984.

- Clothes for a Summer Hotel: A Ghost Play. New York: New Directions, 1983.

- Steps Must Be Gentle. New York: Targ, 1980.

- A Lovely Sunday for Creve Coeur. New York: New Directions, 1980.

- The Two-Character Play. New York: New Directions, 1979.

- Vieux Carre. New York: New Directions, 1979

- Small Craft Warnings. London: Secker & Warburg, 1973.

- Dragon Counting, A Book of Plays. New York: New Directions, 1970.

- In the Bar of a Tokyo Hotel. New York: Dramatists Play Service, 1969.

- Kingdom of the Earth. New York: New Directions, 1968.

- The Mutilated. New York: New York Dramatists Play Service, 1967.

- The Eccentricities of a Nightingale. New York: New Directions, 1964.

- Grand. New York: House of Books, 1964.

- The Milk Train Doesn’t Stop Here Anymore. New York: New Directions, 1964.

- Five Plays . London: Secker & Warburg, 1962.

- The Night of the Iguana. New York: New Directions, 1961.

- The Fugitive Kind. New York: American Library, 1960.

- Period of Adjustment. New York: New Directions, 1960.

- Garden District. London: Secker & Warburg, 1959.

- Sweet Bird of Youth. New York: New Directions, 1959.

- Orpheus Descending. London: Secker & Warburg, 1958.

- Suddenly Last Summer. New York: New Directions, 1958.

- A Perfect Analysis is Given by a Parrot. New York: New York Dramatists Play Service, 1958.

- Cat on a Hot Tin Roof. New American Library, 1955.

- Camino Real. Norfolk: New Directions, 1953.

- The Rose Tattoo. New York: New Directions, 1951.

- I Rise a Flame, Cried the Phoenix. Norfolk: J. Laughlin, 1951

- Summer and Smoke. New York: New Directions, 1948.

- American Blues. New York: New York Dramatists Play Service, 1948.

- You Touched Me! New York: S. French, 1947.

- A Streetcar Named Desire. New York: New Directions, 1947.

- 27 Wagons Full of Cotton, and Other One Act Plays. Norfolk: New Directions, 1945.

- The Glass Menagerie. New York: New Directions, 1945.

- Battle of Ages. Murray, Utah: 1945.

Fiction

- Short Stories. New York: Ballentine, 1986.

- It Happened the Day the Sun Rose. Los Angeles: Sylvester and Orphanos, 1981.

- Moise and the World of Reason. New York: Simon & Schuster, 1975.

- Eight Moral Ladies Possessed. New York: New Directions, 1974.

- One Arm, and Other Stories. New York: New Directions, 1967.

- The Knightly Quest. New York: New Directions, 1966.

- Three Players of a Summer Game . London: Secker & Warburg, 1960.

- Hard Candy. New York: New Directions, 1959.

- The Roman Spring of Mrs. Stone. London: J. Lechmann, 1950.

Poetry

- Androgyne, Mon Amour. New York: New Directions, 1977.

- In the Winter of Cities. Norfolk: New Directions, 1956.

- Five Young American Poets. Norfolk: New Directions, 1944.

Other

- The Notebook of Trigorin: A Free Adaptation of Anton Chekhov’s The Sea Gull. New Directions, 1997.

- Five O’ Clock Angel: Letters of Tennessee Williams to Maria St. Just, 1948-1982. New York: Knopf, 1990.

- Where I Live. New York: New Directions, 1978.

- Letters to Donald Windham. New York: Holt, Rinehart, 1977.

- Memoirs. Garden City: Doubleday, 1975.

- Baby Doll: The Script for the Film. New American Library, 1956.

- Lord Byron’s Love Letter. New York: Ricodi, 1955. (Libretto by TW).

- Blue Mountain Ballads. New York: Schlimer, 1946.

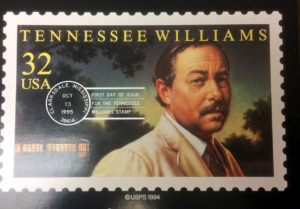

Tennessee Williams: A Biography

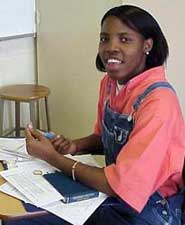

by Don’dria Moore (SHS)

Thomas Lanier Williams was born on March 26, 1911, in Columbus, Mississippi. What is so interesting about his birth is that he was delivered in his grandfather’s Episcopal Church in Columbus, but he later converted to Roman Catholicism (Falk, 14). He was born to Edwina Dakin and Cornelius Coffin Williams, the second of three children and the first boy. His siblings were Rose (his sister) and Walter, known as Dakin (see 2000 phone interview with Dakin below).

When Williams was small, he stayed with his grandparents Rev. Walter E. Dakin and Rose Dakin (see amazing interview with his brother Dakin below), who had by then moved to Clarksdale, Mississippi. According to Falk, Williams moved fifteen times in sixteen years. Finally, he moved back with his parents when they moved to St. Louis in 1919 (Skates and Sansing, 357).

Throughout his life, Tennessee always had a feeling that he wanted to be a writer. It was not until the age of eleven that this desire was recognized when his mother bought him an old type writer . At age fourteen Williams said he was a “dedicated writer” (Falk 21). At age sixteen he wrote an essay called” Can a Good Wife be a Good Sport?” which won third prize and won him five dollars. Also at sixteen, he wrote and published “The Vengeance of Nitrocris” (Cash). He also won many high school advertisement contests.

Tennessee Williams attended the University of Missouri where he decided to become a playwright ( Playwright Tennessee Williams site). He won honorable mention for Beauty is the World, his first play (Bloom 151). While he was at the University of Missouri, his father insisted Williams drop out because he was ashamed of his son’s achievement in the arts in school.

Williams then went to work at the International Shoe Company, where he was a warehouse clerk. There he met Stanley Kowalski, a character he placed in A Streetcar Named Desire(Playwright Tennessee Williams). Williams worked all day and wrote plays and stories all night, which eventually caused him to have a nervous breakdown.

As a result of the breakdown, he went again to stay with his grandparents in Memphis, Tennessee (Falk 22, 23). While staying with his grandparents, Williams produced his first one-act play Cairo, Shanghai, Bombay! (Cash). After the play was produced and published, Williams decided to enroll in Washington University. There his grandmother paid for him to attend.

Williams met Willand Holland, who was the director of Mummers, an experimental theater. Holland introduced Clark Mills McBurney to Tennessee, who introduced Williams to other poets. . Williams and McBurney started a friendship which led them to the “Literary Factor” in McBurney’s basement, where Williams was first really introduced to long plays. A tragic family event occurred, and Williams had to leave Washington University. His sister Rose had an operation on a prefrontal lobotomy from which she never recovered.

In 1937, Williams entered and finally graduated from the University of Iowa in 1938 (Falk, 22). In 1982 he received an honorary degree from Harvard University (Bloom, 154).

After graduating from college, Williams found some work, but then he lost his job. He felt forced to go to New Orleans, where he changed his name from Tom to Tennessee. He got his name from a roommate in college who called him Tennessee because Williams had lived in Tennessee (Playwright Tennessee Williams).

The Field of Blue Children was the first book written by Tennessee. He became an itinerant writer, moving from Chicago to St. Louis to New Orleans to California and finally Mexico. Tennessee earned a little fame from a Group Theater prize of $100 for one-act plays. One of those one-act plays was American Blues.

The following year Williams received $1000 for a Rockefeller Grant. The grant gained him attention and Williams received a contract from Metro Goldwyn Mayer or MGM for six months, earning a pay of $250 weekly. During the time he worked for MGM, he wrote The Glass Menagerie, which was rejected by MGM. That same year his grandmother Rose died form cancer.

Williams decided to re-write the play and publish it.The Glass Menagerie opened in Chicago for the first time. Between 1945 and 1952 he wrote many plays such as A Streetcar Named Desire in 1947 ,27 Wagons of Fall Cotton and Other Plays in 1946, The Cat on the Hot Tin Roof, The Rose Tattoo, and You Touched Me in 1945 (Falk 14,15).

In 1952, Williams was elected into the National Institute of Arts and Letters. Tennessee wrote his plays from his experience and his childhood and his inspiration came strictly from the South (Falk 22). Nevertheless, he was influenced by Frederico Garcia Lorea, Arthur Rimband, Hart Cane, and D.H. Lawerance’s work (Cash).

Tennessee received his first Pulitzer Prize in 1948 for A Streetcar Named Desire. He also received a Pulitzer Prize in 1955 for Cat on a Hot Tin Roof . He also had some of his plays, including The Glass Menagerie in 1950, A Streetcar Named Desire in 1951, The Rose Tattoo in 1955, Baby Doll in1956, Cat on the Hot Tin Roof in 1958, Suddenly Last Summer in 1959, and others made into films.

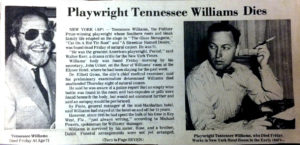

It is no secret that Williams was a homosexual. He died on February 25,1983, in a hotel in New York City. The press and some books say he died from choking on a medicine top, but his brother Dakin says he was smothered by a pillow because he didn’t change his will (See interview below). Tennessee Williams lived from 1911 to 1983.

In 2017, he was inducted in to the Mississippi Arts + Entertainment Experience Hall of Fame.

Reviews

A Review of The Glass Menagerie

by Don’dria Moore (SHS)

The Glass Menagerie takes place in an apartment in St. Louis, Missouri, in 1944. The play is sort of a biography of Tennessee Williams’s life. The characters in this play lived their daily lives during the Great Depression (1930s). The main characters in the play are Tom Wingfield, who works at a warehouse and is a frustrated poet; Amanda Wingfield, the mother who is attached to bromides and fantasies and really lives in the past; Laura Wingfield, an overly-delicate sister, who spends most of her time listening to phonograph records and rearranging her glass animals collection; and Jim O’Connor, an Irishman and a godly gentleman and a high school hero. The real life characters are Tennessee Williams as Tom Wingfield, Edwina Williams as Amanda Wingfield, and Rose Williams as Laura Wingfield. The characters in the play are similar to Williams’ real life Laura, who is shy and crippled in the play, is Rose, Williams’s sister who had mental problems in real life.

The Glass Menagerie has Amanda, the mother, living in the past. She keeps talking about the eighteen gentlemen callers she once had. She gets angry because she had chosen Tom and Laura’s father, and he turned out to be a “drunkard.” So she now tells the children about the gentleman callers she didn’t marry who became rich. Amanda basically lives in the past in this play and hopes that Laura, her daughter, will make better choices.

Laura is a bit mysterious in the play because she doesn’t know what she wants to do. However, her mother wants her to have a gentleman caller. Laura likes to clean her glass animals (thus the title) and they are a symbol for Laura herself, delicate and fragile. Tom arranges for Laura to have a gentleman caller named Jim O’Connor, and. at first, she’s shy and doesn’t want to talk. Jim and Laura get to know each other, but then he breaks her heart when he tells her he’s engaged to Betty. Laura feels very sad that Jim is engaged; Her mother, of course, fusses at Tom for not knowing that Jim is engaged when he brought Jim home (as his mother had asked him to do).

Tom, an interesting character, goes through a lot. He works everyday at International Shoe Company, making $65 a month and trying to take care of his family. The problem Tom has is that he’s always saying he is going to the movies, but instead he goes to a bar/gambling hall. His mother fusses at him about lying, and she fusses at him for smoking. Tom did find his sister a gentleman caller but as mentioned the problem is that he’s engaged. Amanda fusses at him about that situation as well. In the end, Tom leaves both his beloved sister and his mother.

In conclusion, this play contains many interesting characters. The one character that stands out the most is Tom. A one definition word that describes him reliable until he can no longer stand the accusations of his mother. Tom serves as narrator and character and brings life to the play by incorporating his own life situations. Tom Wingfield (alias Tennessee Williams) tells a sad. but poetic story, of life in the beautiful play The Glass Menagerie.

Phone Interview with Dakin Williams, 2000

by Don’dria Moore (SHS)

Don’dria: Mr. Williams, did you and Tennessee, your brother, have a good relationship when you were young?

Dakin: My brother Tennessee and my sister Rose had a great relationship. I (Dakin) never really had a close relationship with Tennessee because I was eight years younger, and Tennessee and Rose were only two years apart. Of course, they wouldn’t want their little brother tagging along everywhere they went. My brother and sister had a very very good relationship until Rose went into a mental institution.

Don’dria: When Mr. Williams was younger, did you have any kind of jealousy?

Dakin: No! Rather more surprise than anything because my father thought Tennessee would never amount to anything, thought that he was going to be a nobody.

Don’dria: Did Mr. Tennessee Williams have a nickname?

Dakin: Yes, matter of fact , my father called him Miss Nancy because my father thought he was a sissy.

Don’dria: Did Mr. Tennessee play any sports?

Dakin: No, because he had a case of diphtheria which made him unable to do some things in early life.

Don’dria: What has been the most important lesson Tennessee William left behind?

Dakin: Street cards would probably be an important lesson because he was a big time gambler. Tennessee thought that people should have more consideration for others; Tennessee did when he wrote some of his plays. Tennessee was a person who had both personalities; he had both man and woman personality. Many of his plays were written in a woman’s version and dealt with their problems. One woman was Blanche DuBois..

Don’dria: Have Tennessee’s plays had an effect on other authors or writers?

Dakin: Yes, Tennessee’s plays have had a lot of effect on many authors and writers. One author was Bill Inge. Bill said, “Tennessee’s success gave me desire.”

Don’dria: If Tennessee was still alive today, what do you think he would write about?

Dakin: He would probably write about his killers. Tennessee wasn’t killed by mistaking a pill top for a pill. He was smothered with a pillow. They used the pill top as an excuse. He was killed because he was going to change his will. More information can be found in His Brother’s Keeper (Dakin’s book).

Don’dria: So do you have any symbols or something that was left over by Mr. Williams?

Dakin: No! I sold all of them at an auction in New York. I sold Shadow Wood for $7500.

Related Websites

- This site from the University of Mississippi is about Tennessee Williams’s life and fame.

- Biography of Tennessee Williams

- Tennessee Williams New Orleans Literary Festival

- Poetry Foundation’s biography of Tennessee Williams

- Interview with Tennessee Williams in the Paris Review

- New Yorker Magazine “The Lady and Tennessee” by John Lahr, 1994

- Tennessee Williams by John Lahr, The New York Times

Bibliography

- Abbott, Dorothy. ed. “The Glass Menagerie: Tennessee Williams“ 4 vol.Mississippi Writers Reflections of Childhood and Youth. Jackson: University Press of Mississippi. 1985. 437-530.

- Akin. Edward N. Mississippi: An Illustrated History. Northridge, California: Publications, Inc., 1987. 139.

- Atkins, Joe. “Tennessee Williams. ‘Moon Lake Casino’ offers a Menagerie ofvision, Mummers.” Clarion Ledger: July 25, 1999. 3H.

- Bloom, Harold ed. Modern Critical Views Tennessee Williams. New York: Chelsea House Publishers, 1987.

- Easterling, Thomas. “Secret Forecast.” Oxford American. Mar/Apr. 2000 9/+

- Falk, Signi. Tennessee Williams 2nd ed 10 vols. Boston, Twayne Publishers, 1978.

- Hogue, Edwina. “Note Taking about Tennessee Williams.”

- Jr. Campbell, Edward D.C. ” Williams Tennessee in Film.” Encyclopedia of Southern Culture. Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina, 1989, 978-979.

- Cash, Eric W. Mississippi Writers. “Tennessee Williams.” [Online] Available

http://www.olemiss.edu/depts/english/ms-writers/dir/williams_tennessee/ - “The Playwright Tennessee Williams.” [Online] Available http://hipp.gator.net/scraplaywright.html.

- Riley. Carolyn. “Williams, Tennessee .” 1(1973) Contemporary Literary Criticism. Detroit, Michigan: Gale Research Company Tower 1973. 70 vols. 367-369

- Skates, John Ray and Sansing David G, “Tennessee Williams.” Mississippi: the Study of Our State. Brandon, Mississippi: Walthall Publishing Company, 1993. 353,357.

- Williams, Dakin. Personal Interview by Dondri’a Moore. May, 2000.