Major Works

- Carnival (drama) 1935

- “Tale of the Blackamoor” (short story) 1936; published in the periodical Challenge

- Let Me Breathe Thunder (novel) 1939

- Blood on the Forge (novel) 1941

- “Death of a Rag Doll” (short story) 1947; published in periodical Tiger’s Eye

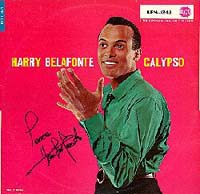

- Calypso Song Book (songs) 1957

- Hear America Singing (nonfiction) 1967

- From These Hills, From These Valleys: Selected Fiction About Western Pennsylvania. Demarest, Jr., David P. (editor), apparently contains short stories by William Attaway

Biography

by Ashley Shrez Odom (SHS)

In Greenville, Mississippi, on November 19, 1911, William Alexander Attaway was born to William S. Attaway, a medical doctor, and Florence Parry Attaway, a teacher (Drapher 56). William Attaway was a member of a migrant professional family. (Lloyd 14) At the age of six, his father moved them to Chicago, Illinois. In his teens, Attaway attended a vocational high school, planning to become an auto mechanic (Drapher 56). According to his daughter Noelle, Attaway saw no future for himself in the world as it was then. One day in English class, however, Attaway read a poem by Langston Hughes. After discovering that Hughes was a black poet, Attaway’s life changed, and he began to apply himself in his school work. He also, for fun, tried his hand at script writing for his sister’s amateur dramatic groups. Upon graduation from high school, Attaway enrolled at the University of Illinois (Lloyd 14) where he was a black tennis college champion (Attaway, Noelle).

The death of Attaway’s father forced him to drop out of college, and he became a hobo for two years. He traveled around the country, working at various times as a seaman, salesman, and labor organizer. Without realizing it, Attaway was gathering material for his later writing. In 1935, Attaway helped write the Federal Writers’ Project guide to Illinois. While working on this project, he became friends with another young Mississippi writer named Richard Wright. Attaway returned to the University of Illinois in 1935, received his degree, and moved to New York. His drama Carnival was produced about this time. In 1936, Attaway published his first story “Tale of the Blackamoor.” He worked odd jobs and even tried acting with his sister Ruth, who later became a successful Broadway actress (Lloyd 14). His literary career actually began under the tutelage of his sister.

In 1939, while performing with the traveling production of Moss Hart and George S. Kaufman’s You Can’t Take It With You, he learned that his first novel Let Me Breathe Thunder had been accepted for publication. Aided by a two-year grant from the Julius Rosenwald Fund, Attaway immediately began work on his next novel, Blood on the Forge, which was published in 1941 (Drapher 56).

Attaway’s novels were well received by critics but did not attract much attention. Drapher believes that this is true because Richard Wright’s Native Son was published about the same time. (Lloyd 15) At any rate, after Blood on the Forge was published, Attaway did not write any more novels. Instead, he wrote songs, books about music, and screenplays. In 1957, Calypso Song Book, a collection of songs was produced. In 1967, he wrote Hear America Singing, a children’s history of popular music in America. William Attaway wrote songs for Harry Belafonte ((in whose home Attaway was married in 1962, Drapher 56), including the famous Day-O Banana Boat Song. Altogether, Attaway wrote over 500 songs. (Cox 107)

In the fifties, he turned to writing for radio, films, and TV. He wrote for such TV programs as Wide Wide World and the Colgate Hour. Attaway was the first black writer to write scripts for TV and films. He wrote Hundred Years of Laughter, an hour long special on black humor that aired in 1964. The hour-long special featured comedians Redd Foxx, Moms Mabley, and Flip Wilson in their first appearances on television.

Attaway lived with his wife, Frances, and his two children, Bill and Noelle, in Barbados for eleven years. His last years were spent in California writing screenplays.

William Attaway, an American novelist, essayist, short story writer, playwright, screenwriter, and song writer, died of cancer in June, 1986 (Drapher 56-57).

Bill Attaway’s Phone Comments about his Father

with Ashley Shrez Odom (SHS)

Bill Attaway remembers his father as being a remarkable man. William Attaway always urged Bill and his sister to excel in everything. Bill recalls his father as referring to the Bible as “the greatest book in the world.” Bill Attaway doesn’t remember a lot of childhood memories, but he does remember the stories that his father told him. He thinks that a lot of his father’s books were written from his experiences in life. Bill Attaway is very proud of his father’s success.

Reviews

A Review of Blood on the Forge

by Ashley Shrez Odom (SHS)

Blood on the Forge is the best book that I’ve ever read. It seemed as if it were a life story of William Attaway. In the novel the three main characters are Big Mat, Chinatown, and Melody. Big Mat is the oldest of the three brothers and is responsible for the family. Without Big Mat, the family would fall apart. The setting is during the Great Migration. The men are looking for work and find themselves in West Virginia working at a steel factory. Big Mat works while his wife Hattie lives back in Arkansas. He promises to send for her as soon as he gets the money. Months pass and Big Mat still doesn’t send for her. Chinatown and Melody begin to think that Big Mat has no intentions of sending for her. They confront their brother and he admits he isn’t going to send for her. He starts living with a Mexican whore whom Chinatown and Melody disapprove of.

They are all ready for a new life. Work in the steel factory wasn’t as a good as they expected. Big Mat no longer reads his Bible, and the brothers begin to fall apart. Big Mat has changed for the worst. Without him, the family isn’t the same. Chinatown and Melody encounter injuries at the steel mill that they can’t recover from. The three brothers separate by souls, not by bodies. They no longer wait for each other after work or go anywhere together. I can’t say if it was because of Big Mat’s change or Chinatown and Melody’s laziness, but the brothers stay separated. This book expresses a lot about working alone where you have no family or friends. Everyone in the book suffers from something: either loneliness, injuries, or lack of money. The men all want to live a better life, but life promises them no hope. I think William Attaway wrote this book to prove that no matter who you are or where you go, you can’t escape the bad things in life.

An E-mail Interview with Noelle Attaway Kirton

by Ashley Shrez Odom (SHS) (April 28, 2001)

What can you tell me about your father’s school days?

Most of this information we do not know. My father rarely talked of his life in the context of when he was a child. Here are a few things that I do know.

Up until the age of 11, my father refused to apply himself at school. Even though his father was a black doctor (not many of those), he saw no future for him in the world then, especially none that school would help. One day while in English Class, his teacher read from Langston Hughes a poem about a young black boy. When the class was told it was a black author, my father’s life changed forever. He said from that day on he applied himself at school and finished early. He went on to complete four years of college in 1 1/2 to 2 years and was mid west black tennis college champion. He then left school and rode the rails and hoboed on the train. It is felt that both of his novels were based on his own experience. He returned to New York and was the original writer for the Colgate Hour, which gave many black performers their first break, including Richard Pryor.

Another childhood story was of him being stabbed by a group of white youths while walking home. He was many miles from his home, and the white hospitals would not help him. He remembered his father telling him that it was when the knife was removed that people bled to death, so he walked the miles home to his father’s black hospital with the knife in his side.

Who was your father’s favorite author?

I do not know who his favorite author was, but I was named after two of his favorites, Noel Langley and My Sweet Antonia by Willa Cather. ( I think that’s her name). Eugene O’ Neill was also a favorite. My mum said he loved the writing of the Bible and Shakespeare as well. He wanted to name my brother Jesse as Jesse Owens was one of his great heroes.

What other things did your father do?

In the Second World War, my father was a captain of a black regiment. He spent much time in North Africa. They worked in high-risk clandestine operations, and the stories I was told seem too far fetched for me to repeat them. But I do know that he received some sort of medal, but I never saw it. He was shot in the hand.

My father marched with Dr. King, and we had papers before the fire which destroyed much of his papers, including a letter from Martin Luther King to my father as a fellow freedom fighter.

Noelle, Bill, Frances, and William Attaway along the beach in Barbados. Photo courtesy of Noelle Attaway Kirton

Here is an interesting story I remembered:

My parents decided to be married in the 50’s. He had been living in Haiti and felt that they could be together in the southern parts of the world. He cabled my mum, she was separated from her first husband and said to meet him in L.A. He had received a large check from the sale of his books and music. He was buying a Cadillac and had over $250 thousand dollars in his pocket. (A fortune then and now but unheard of for a black man) They would drive over the Mexican border together and start their new life. Well, as he drove through Texas, he was stopped by the State police, robbed, and sold to the Mexican police for six months to build roads. He was chained and slept on the road side until they released him on the American border with nothing but his life. Meanwhile, my mother figured that he chickened out again and accepted a marriage proposal from long time admirer jazz musician Tony Scott. My father showed up on their wedding night. Those details I do not know. I do know that Tony accepted a job with the State department as a jazz ambassador in the Asian countries, and he and my mum left.

Tell me what you remember about your father and your family life.

My father married my mum when he was 55 or so. She was a white New Yorker whom he loved for over 20 years. It was only in the 60’s that they felt brave enough to risk the interracial marriage. Soon after my brother and I were born, death threats came, and he moved us to the Caribbean. It was at this point he stopped writing his deep thoughts and made money ghost writing many movies including “The Hustler.”

Within three years my father had flown to Japan (I do have quite a few of the cables he sent her keeping in touch), and they renewed their relationship and then became openly a couple. They did go to Haiti for a few years.

My father left Mississippi at 6 years old and moved to Chicago where his father could practice medicine. He felt nostalgia for the South but never wanted to take us there and did not like me going even to Texas in the 80’s.

My father’s closest friends included Harry Belafonte (whom he wrote many songs for) and Sidney Poitier. The three of them owned a small restaurant in the village in New York called the Sage. This was before any of them were famous. There are many great stories from those days that include everyone from the Harlem Globe Trotters to the Mob.

Thanks to Noelle Attaway Kirton for the Attaway family photos and the interview above.

Timeline

- 1911 — November 19, William Attaway was born to William S. Attaway, a doctor, and Florence Parry, a teacher

- 1935 — Helped write the Federal Writers’ Project guide to Illinois

- 1935 — Wrote Carnival (drama)

- 1936 — Published “Tale of the Blackamoor” (short story) in periodical Challenge

- 1936 — Received B.A. degree from the University of Illinois

- 1939 — Published first novel Let Me Breathe Thunder

- 1941 — Published second novel Blood on the Forge

- 1947 — Published “Death of a Rag Doll” (short story) in periodical Tiger’s Eye

- 1950’s – Wrote for radio, films, and TV

- 1957 — Wrote Calypso Song Book

- 1962 — December 28 married Frances Settele and had two children, a son and a daughter

- 1964 — April 27 son Bill was born

- 1966 — July 14 daughter Noelle was born

- 1966 — Went to Barbados with family for vacation and they lived there for eleven years

- 1967 — Published Hear America Singing (non-fiction)

- 1985 — Suffered a heart attack

- 1986 — June 17, William Attaway died of cancer

Related Websites

- This Ole Miss Writers Page lists Greenville as birthplace, but no other info is available

- Reviews for Blood on the Forge on Amazon.com.

- The African American Registry has biography of Attaway.

- enotes.com has important biographical information about Attaway in literature.

- New York Review of Books presents bio and sells Blood on the Forge.

- Excerpt in journal from From Pastoralism to Industrial Antipathy in William Attaway’s Blood on the Forge by Philip H. Vaughan.

- Excerpt in journal called “William Attaway’s Blood on the Forge: The Death of the Blues” by Edward E. Waldron.

- General Electric Theater’s play Winner by Decision (1955) was directed by William Attaway.

- Interesting Article about Attaway in American Naturalistic and Realistic Novelists: a biographical dictionary.

- Information about liner notes for Harry Belafonte’s music written by Attaway

Bibliography

- Attaway, Bill. Telephone Interview. 30 April. 2000.

- Cox, James L. Mississippi Almanac 1997-1998. Computer Search & Research, 1997. 107.

- Drapher, James P. Black Literature Criticism. Volume I. Gale Research Inc., Detroit -London, 1992. 56-74.

- Kirton, Noelle Attaway. “Information on William Attaway.” [email protected] from [email protected], May 3, 2000.

- Lloyd, James B. Lives of Mississippi Authors, 1817-1967. Jackson, University Press of Mississippi, 1981. 14-15