Major Works

- Flags in the Dust (1973)

- The Reivers (1962)

- The Mansion (1959)

- The Town (1957)

- Big Woods: The Hunting Stories of William Faulkner (1955)

- A Fable (1954)

- Requiem for a Nun (1950)

- Knight’s Gambit (1949)

- Intruder in the Dust (1948)

- Go Down, Moses (1942)

- The Wild Palms (1939)

- If I Forget Thee, Jerusalem (1939)

- The Unvanquished (1938)

- Absalom, Absalom! (1936)

- Pylon (1935)

- Light in August (1932)

- Sanctuary (1931)

- A Rose for Emily (1930)

- The Hamlet (1930)

- As I Lay Dying (1930)

- The Sound and the Fury (1929)

- Sartoris (1929)

- Mosquitoes (1927)

- Soldier’s Pay (1926)

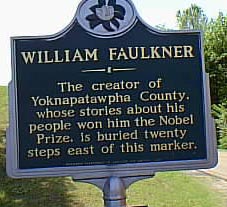

Biography of William Faulkner (1897-1962)

by Toyin Larinde (SHS)

William Faulkner is recognized as one of America’s greatest novelists and short story writers of the 20th century. Faulkner was born in New Albany, Mississippi, on September, 25, 1897. His great-grandfather had moved from Tennessee to Mississippi, where he was a plantation owner, colonel in the Confederate army, railroad builder, and author of the popular novel The White Rose of Memphis.

Faulkner’s family moved from New Albany to Oxford, Mississippi, when Faulkner was five. Oxford, the home of the University of Mississippi, was to be his home for most of his life. In school Faulkner was a mediocre student, and he quit high school in tenth grade. However, he read widely and wrote poetry. At the outbreak of World War I Faulkner was rejected by the American Air Force because he did not meet the height and weight requirements so Faulkner enlisted in the Canadian Air Force. Although he did not see combat, he was made an honorary second lieutenant in December, 1918.

After the war Faulkner was admitted to the University of Mississippi but did not complete his freshman year. Student publications, however, furnished him an outlet for his first stories and poems.

In 1921 Faulkner went to New York City and tried to make contacts in the publishing world but was unsuccessful. On his return to Mississippi, Faulkner was appointed post master in Oxford of the university post office in 1922 and continued this job until 1924. In 1924 Faulkner met novelist and short story writer Sherwood Anderson, who impressed him and urged him to take up fiction. In six weeks Faulkner finished his first book Soldier’s Pay, which was a self-conscious book about the lost generation. His first successful novel, The Sound and the Fury, was published in 1929. The 1930’s were Faulkner’s most productive times because he produced As I Lay Dying in 1930, Sanctuary in 1931, Light in August in 1932, Absalom! Absalom! in 1936, The Unvanquished in 1938, and The Hamlet in 1940.

Faulkner did not gain real recognition until he was awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1949. After this award, Faulkner became pretty much of a public figure, eventually even being asked (and accepting) an invitation by the U.S. State Department to go on goodwill tours throughout the world.

After 1949 Faulkner wrote at an increased pace but with diminishing power. His later works include Knight’s Gambit (1949), which is a collection of detective stories; Requiem for a Nun (1951), which is a play with commentary; and A Fable(1954), an allegory with a World War I background. He also wrote The Town (1957) and The Mansion(1959) to complete the “Snopes” trilogy. His last novel was The Reivers(1962), a nostalgic comedy of boyhood. Faulkner died of a heart attack in his home called Rowan Oak in Oxford, Mississippi, on July 6, 1962.

In his works William Faulkner used the American South as a microcosm for the universal theme of time. Faulkner saw the south as a nation by itself. Faulkner described the South through families who often reappear from novel to novel. These reappearing characters usually grow older and cannot cope with the social change: a common theme (disillusionment) of writers of that time.

Faulkner writes with an uncommon method of handling chronology (sequences) and of point of view. He often forces the reader to piece together events from a seemingly random and fragmentary series of impressions experienced by a variety of narrators. Faulkner’s style often strains conventional syntax, piling clause upon clause in an effort to capture the complexity of thought. Faulkner’s writing diverges from that of his realistic contemporaries such as Hemingway.

Faulkner was awarded the Pulitzer Prize in Fiction in 1955 for “A Fable” and in 1963 for “The Reivers,”

William Faulkner was inducted into the Mississippi Arts + Entertainment Experience (The MAX) Hall of Fame in 2017.

Reviews

A Discussion of Faulkner’s Destructive Idyll in The Sound and The Fury

by Sara Nagel (SHS)

In many literary works one of the characters is a mooning philosopher who becomes disenchanted with the present and romanticizes the past. In William Faulkner’s The Sound and the Fury, Quentin Compson’s reverence and longing for the past create in him a detestation of modern society which eventually leads to his destruction.

Quentin Compson values the ideals, philosophies, and traditions of the past. He believes strongly in the virginity requirements for unmarried girls. Because of this belief, Quentin is horrified and shocked to learn of Caddy’s promiscuity. Quentin’s concept of honor and “protecting the family name” are so highly ingrained that he feels it necessary to challenge Dalton Ames, the boy who first violated his sister. (In this incident Quentin is beaten soundly.) Likewise, when Quentin is strolling around with the little Italian girl and is assaulted by her protective brother Julio, Quentin is not offended but relieved to find someone who believes as he does in protecting his sister.

After the invitation to Caddy’s wedding arrives at his dorm, Quentin realizes the permanence of his separation from Caddy. Quentin enjoyed spending time with his sister and being in her company. Remembering these times with her, he comes as close to happiness as is possible for him. This remembered joy, which comes at a time of relative bleakness, reveals to Quentin that which his father had passed on to him and has lain dormant for two years: a destructive , nihilistic view of the present and an idyllic view of the past.

Upon realization of these “truths,” Quentin can no longer function as part of the modern world, nor does he wish to. Quentin wants to return to the past, but cannot. He smashes his watch, runs from the clock-laden bell tower, and hides from the school bells, but to no avail. Time passes; the day goes by. If it is impossible to go back and dishonorable to go forward, one must simply stop. Upon the basis of “truth” and rationality, Quentin Compson chooses to commit suicide and end time.

Thus, Quentin Compson’s reverence and longing for the past create in him a detestation for modern society which eventually leads to his destruction . It is in change that one should find hope, but Quentin cannot adjust to the world as it now is. Quentin’s situation holds little potential for hope, leaving him little reason to carry on. This inevitability of destruction is one of the most powerful themes in Faulkner’s The Sound and the Fury.

Quentin and His Time-Fear

by Kurt Spurlock (SHS)

William Faulkner’s The Sound and the Fury spans a time of several years through clever manipulation of time in the thought processes of its characters. Flashbacks abound, and memories flit forth and back often without warning. Quentin particularly finds time and the past both horrifying and ubiquitous agents of decomposition but also construction. His past virtually becomes his present in an attempt to subjugate the now of his sad existence. Quentin’s preoccupation (obsession, perhaps) with the past helps illustrate the novel’s themes of the destructive nature of a hereditary curse and the progression of time as a force of the erosion of man’s soul.

Quentin Compson possesses a great penchant for the remembrance of past events, a trait which implants in him both a great reverence for his family’s lore and honor and a painful reaction to the realizations, often harsh, that maturity brings. It is not just any watch that he breaks but that of his grandfather, a distinctly physical reminder of times of yore. Cognizance of time’s metered flow sears his mind to the point of breaking and braking. He physically fights to protect what he views as Caddy’s sullied honor. It pains him to see shame brought to his family name and particularly to his sister. He desperately endeavors to cling to an ancestral nobility of behavior in a world shifting from it. But the world, just as Gerald does, beats him back down when he flares up in defense of paladinity.

It is the world that squelches displays of what Quentin finds honorable, that leaves him feeling alienated from everything. The past is not so glory-filled, he must discover, particularly his own. Though awareness typically brings with it maturity and independence, it also crushes the simplicity of youthful innocence. Caddy’s sexual encounters leave Quentin behind and uncomprehending, forcing him to acknowledge sexual pressures. He resorts to falsely admitting incest just to maintain Caddy’s presence. He is one of the dead on time’s battlefield.

Quentin is acutely aware of time’s omnipresence. He reels at its quantifiability and incessant tick tick tick tick. Faulkner, through Quentin, vividly illustrates the pain time brings through both the events left in its wake and its future victims. The sadly, though not necessarily mistaken) nihilistic Quentin views life, as did Tennessee Williams, as “the process of burning oneself out” and time as “the fire in which we burn.”

The Tragedy of Two Lost Women

by Amy Krans (SHS)

The Sound and the Fury by William Faulkner is a novel that shows the tragedy of a deteriorating family. The novel is further focused on the tragedy of two lost women: Cady and her daughter Quentin. The tragedy of these two lost women explains and reveals the central theme a Southern family in decline.

The Sound and the Fury revolves around Caddy’s life. In each section of the novel, each character refers to Caddy in both good and bad ways. Caddy serves as the mother figure in the Compson home. Caddy becomes the one who nurtures Benjy and Quentin. Because Caddy is the mother figure, there is no one to give her the love and affection a mother would. Consequently, Caddy becomes flirtatious as she reaches sexual maturity. These changes in Caddy are destructive to both Benjy and Quentin. Caddy’s growth and discovery of her sexuality become Quentin’s ultimate downfall. Benjy is even further lost. Eventually, Caddy’s name is forbidden in the Compson household, and Caddy’s illegitimate child is left to bear the burden. Caddy becomes “lost” in the minds of her family.

Quentin, Caddy’s daughter, falls into an uncontrollable fate. Quentin grows up living with her grandmother, Uncle Jason, and Dilsey. Quentin, like her mother, feels no love from her “mother figure.” Moreover, her hateful uncle takes out his bitterness towards Caddy on Quentin. Jason denies Quentin money sent to her from her mother and uses his control over her destructively. The only person Quentin feels affection from is Dilsey. However, Quentin rejects the affection. Like her mother, Quentin rebels and runs around with men. Quentin, unlike Caddy, is embarrassed by Benjy and is mean to Dilsey. She lacks her mother’s love and compassion. Quentin’s behavior not only represents the Compson deterioration, but the change in modern society. In the end, Quentin runs away with a show man. She too becomes “lost.”

The tragedy of both Quentin and Caddy reveals the central theme. The two women represent destruction of themselves, the Compson family, and of society. Moreover, the novel is focused on Caddy because each destructive act traces back to Caddy. Quentin’s suicide, Jason’s behavior towards Miss Quentin, and Benjy’s unhappiness all link back to Caddy. Through both of these characters, the reader is able to see the theme: the destruction of a Southern family brought on by guilt and remorse.

Review of Requiem for a Nun by William Faulkner

by Daniel Kerr (SHS)

Requiem for a Nun, written by William Faulkner, is a strange synthesis between a play and a story that leads the reader into a conflict between truth and false-hood. William Faulkner, known for his literature around the world, presents to us a play, interspersed with introduction-like prose, that contains within it a mystery. The book is strangely put together. At the beginning of each act, there is a section of prose. These sections have little to do with the plot of the play but serve as a history to the places where the action takes place. The first such passage, for example, describes the creation of Jefferson city, which is where the first act takes place. Then, suddenly the book switches over to play format. These transitions are rather confusing, as they are rather incongruous leaps from one subject to another.

The play begins in a court-room where a black woman pleads guilty to the murder of an infant. She is then sentenced to death. The play then jumps to the residence of the family of the murdered child. There, Stevens, the condemned woman’s attorney, and Temple, the mother of the murdered child, are having a rather heated discussion. Stevens believes that the entire truth of the murder was not told at the trial, and he urges Temple to tell him what happened. At first Temple refused, but after some time she decided to tell all of what happened. They then go to Jackson, so Temple can tell the Governor all that happened in an attempt to have the sentence of the black woman commuted. Temple, after much coercing, tells her awful story.

The play itself is rather unremarkable, centered around the idea of the importance of the truth. The action plays upon the conflict between Stevens and Temple, as the lawyer probes for the truth of the situation. The author uses a good deal of for-shadowing to keep the reader interested until the main mystery is revealed. This is certainly not the best work of William Faulkner, and it isn’t the best play I’ve read. Certainly though, it isn’t the worst I have read. I consider it a “closet-play,” that is, it is a play meant to be read, rather than watched. However, it is entertaining enough to read, and if you have read every-thing else by Faulkner, you might as well read this.

Related Websites

- Where was Colonel Falkner shot? by Jack D. Elliott, Jr., 2012

- On Shiloh’s Battle Ground— a letter by Sallie Murry Falkner (1850-1906) of Oxford , Mississippi, and formerly of Ripley, Mississippi, to her father, Dr. John Y. Murry, Sr. (1829-1915) of Ripley, describing her August 1897 visit to the Shiloh National Military Park with her husband, John W. T. Falkner (1848-1922). Transcribed by Jack D. Elliott, Jr.

- Information about Faulkner’s books, short stories, speeches, poetry, letters and other writings. It also has information about his life and adopted hometown. It also has a link to other Faulkner sites information about Faulkner’s play writing career and commonly-asked questions about Faulkner.

- Home page for the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1949 awarded to William Faulkner.

- Faulkner’s Nobel prize speech is cached here.

- Reading group guides for The Sound and the Fury, As I Lay Dying, and Absalom! Absalom!

- Books and writers site gives interesting info about films made from Faulkner’s books and screenplays that Faulkner wrote.

Bibliography

- Arensberg, Mary, and Sara E. Schyfter. “Hieroglyphics in Faulkner’s ‘A Rose for Emily’/Reading the Primal Trace.” Boundary 2 15.1-2 (Fall 1986-Winter 1987): 123-34.

- Inge, M. Thomas (ed.) William Faulkner : The Contemporary Reviews. The first comprehensive collection of contemporary published reactions to the writing of William Faulkner from 1926 to 1962, these articles document the response of reviewers to specific works, and chronicle the development of Faulkner’s reputation among the nation’s book reviewers. Cambridge University Press, 1997.

- Faulkner criticism in the 1990’s.